This article was first published by cycads.

A few months ago, Alicia asked me why science fiction was such a boy thing and what is the point of the genre. I cobbled together an answer about science fiction being used to create a narrative space removed from the here and now into which pertinent questions and ideas can be tried out. Science fiction might not be science, but it does have an experimental edge. As for the boyish enchantment of the genre, I imagine that it has something to do with love of grand ideas and machines rather than human relationships and emotions. Then I remembered reading somewhere about women’s science fiction, and yet still feminist science fiction. A quick web search led us to Feminist SF, and I recommend a browse.

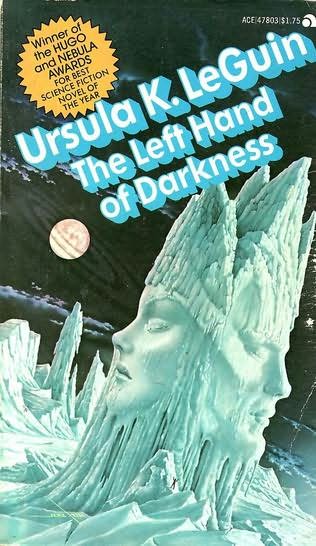

I have long been a fan of Ursula Le Guin, since reading her Wizard of Earthsea at primary school. I was enrapt by her bringing imagined cultures and worlds to life through her writing: a skill, I later learned, was informed by her understanding of anthropology. Quite apart from Earthsea, The Left Hand of Darkness is considered a cornerstone of feminist science fiction: not only does Le Guin conjure up a fascinating world in which to immerse the reader, she also asks us to think deeply about sex and gender.

The Left Hand of Darkness is about Genly Ai, a man sent as an envoy of a collectivity of human-inhabited planets called the Ekumen to an arctic world they know as Winter, and known to its inhabitants as Gethen. The book is an account of Ai’s mission to Gethen to begin interplanetary dialogue. Interleaved in Ai’s account are logs from a previous investigative mission, collected folk tales and the excerpts from the diary of a Gethenian friend. These help to give the reader a number of points of views in parallel. This is not Flash Gordon territory: Ai has no ray gun, his ‘ship’ is impounded in a Gethenian warehouse, he’s black, and the Gethenians, while fairer skinned, are not white.

The Gethenians are human, but with one major difference: they are ambisexual. In Gethenian society there are no men or women, just people, and each has the potential to father or mother children. Most of the time, Gethenians are in an androgynous, neutral state, but once every 26 days they enter kemmer, a state of sexual readiness. In kemmer, a Gethenian becomes temporarily male or female based on hormone levels, and there is no telling which one might become, except that kemmering pairs tend to go into kemmer together and as opposite sexes. Lineage is traced through the parent of the flesh (‘mother’). There is no marriage, but an informal vow of kemmering exists for long-term partnerships. Employers give each employee leave from work during each one’s kemmer, a kind of romance/sex holiday. Friendship becomes a serious business, when any good friend could be one’s next sexual partner. Prostitution is absent from Gethen, and unpaired kemmerings can go to their local kemmer house to satisfy their needs with others.

It is certainly intriguing to dive into this thought-experiment of a world without gender. Le Guin skilfully spins this tale as neither a utopia of gender barriers overcome or a dystopia of circus oddities. In fact, the Gethenians consider Ai, who ‘carries his genitals always outside of his body’, a pervert for his permanent masculinity. Through Ai’s eyes, we see that it is not easy at all to overcome this ingrained bipolar distinction of sex. Ai is appalled to see politicians, whom he thinks of as men of power, gossiping and plotting like old women. He sees his landlady as an old woman, but, when asking her of her children, is surprised to hear that she has never borne a child, yet has sired two. He is amused to hear the king is pregnant. His difficulty is ours, always having to define each action, word or appearance as masculine or feminine, despite knowing that such terms are meaningless. At one point a Gethenian innocently asks Ai what women are like. He struggles to describe the whole idea so taken for granted by him, yet unknown to the questioner. In the end he is limited to meaningless generalisations, ‘They tend to eat less’.

When one becomes more accustomed to the situation on Gethen, philosophical issues begin to be seen. The fact that any Gethenian can be pregnant makes them less free than men, yet because this might happen to anyone they are more free than women. In fact, Gethenian life tends to be communal, centred on the ‘hearth’, a partially related group of Gethenians raising children together. However, a darker side of Gethenian communalism is seen in the labour camps for undesirables. The lack of sexual dualism also leads to lack of dualism in other areas. The old Gethenian religion is based on nothingness and praises ignorance, seeing them as just as important as existence and knowledge. For Gethenians, the undivided whole is important: the unity of darkness and light. On Gethen, there is no sense of Other. This means that there have be no real wars in their history, just the odd skirmish, foray or assassination. Likewise, the lack of sense of Other makes Gethenians uninquisitive, developing technology at a slow, steady pace. The cult of Yomesh, a younger religion, is gaining pace, bringing nascent dualistic thought to Gethen. Along with comes technological advancement, but also a jingoism of the need to prove superiority over the Other.

I finished the book with a sense of how deeply our division of sex and gender influence the smallest parts of our lives. I imagine Le Guin would have writtenThe Left Hand of Darkness differently today. It was originally written in 1968, and its stance is neutral and open, certainly not feminist flag waving. However, I found this open approach, not pushy or preachy, to be the more compelling. How does sex shape our minds, our world?

Hmm. I wonder if Anne McAffrey’s “The Ship Who” series would count as sci-fi? It’s about people with strong minds but horrific physical handicaps becoming “Ships with Brains” and in my opinion captures both human emotion and cool machinery beautifully. I loved the whole series. ^^

I admit I haven’t read anything by McCaffrey, but she is known as a science-fiction writer. Is this the book in which children born with severe physical disabilities have their brain installed in spaceships, which become their new bodies?

Pingback: Resource Roundup: Margaret Atwood, Octavia Butler, Ursula K. Le Guin « Sci Femme

Pingback: Author Worth Reading: Ursula K. Le Guin « Books Worth Reading

This article is very important to me, and I like it very much, I will add it to my favorites.