I apologize for the click bait headline: no, he was not! I was, however, revisiting some fascinating work done by the syriacist Hidemi Takahashi on proper names in the Christian documents and inscriptions of Tang dynasty China (here, here and here). Three Chinese characters in one document seem to refer to Jesus’ disciple Simon Peter as ‘Solid-Peak Monk’.

Christianity first came to China during or just before the Tang era. The first Christians in China were most likely traders who came overland along the famous Silk Road to the Tang capital city of Chang’an (today’s Xi’an). They were adherents of the Church of the East, who prayed in Syriac but mostly spoke Iranian and Turkic languages.

In the great hoard of manuscripts discovered at the Dunhuang caves complex are those belonging to this first Chinese church. One of these is the eighth-century Zūnjīng (尊經 ‘The Book of Honour’), which is a rather grand name for what is essentially two lists of names. The first list in Zūnjīng is of biblical characters and saints, while the second is list of Christian books, including some other documents found at Dunhuang. It seems that the purpose of Zūnjīng was to provide a crib sheet for those translating Christian texts into Chinese to show which characters should be used for certain names.

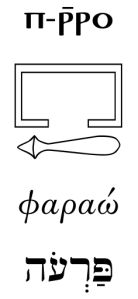

The entry for ‘Solid-Peak Monk’ appears in Zūnjīng‘s list of names. The entry simply reads Cénwěn Sēng (岑穩僧 literally ‘solid peak monk’). From other uses, it is clear that the name Cénwěn should be understood as ‘Simon’. In the Middle Chinese pronunciation of the Tang era, it would likely have been pronounced /d͡ʒiɪm ʔuənX/ or /tʂɦəm ʔun’/ (different sources reconstruct it differently). The Japanese reading of the characters as shimu’on (しむおん) upholds this kind of pronunciation, and Japanese readings often give a good insight into the pronunciation of Middle Chinese. Seeing as the liturgical language of the first Chinese Christians was Syriac, this fits with the Syriac for ‘Simon’, which is Shem‘ōn (ܫܡܥܘܢ, exactly following the Hebrew Shim‘ôn שמעון, ‘he has heard’). If the Simon in question is the Simon Peter whose nickname means ‘rock’ (from the Greek Petros Πέτρος, given by Jesus in the punning dialogue of Matthew 16.13–20), then the literal meaning of the characters 岑穩 as ‘solid peak’ also makes sense. All of this is rather linguistically satisfying.

The name ‘Peter’ sounds like just that, a name, to most us, and we forget that it is a rocky nickname. The New Testament gives us an alternative version of the name, often written Cephas in English Bibles. This represents Kēphas (Κηφᾶς) in the Greek text. This is the Aramaic word for ‘rock’: Kêfâ (כיפא ܟܐܦܐ). He gets a final sigma in Greek to make it sound more manly, as an alpha ending is womanly (Jesus’ name got its final ‘s’ for the same gendered reason). As Syriac is a variety of Aramaic, Simon Peter is more usually called Shem‘ōn Kēfā (ܫܡܥܘܢ ܟܐܦܐ). It would be natural for Christians who prayed in Syriac to have carried Peter’s name to China not as the Greek Petros, but the Syriac Kēfā, but that is not what the scribe of Zūnjīng gave us.

The Chinese sēng (僧) is used for Buddhist monks. Thus we literally have ‘Simon the Buddhist monk’. The Chinese word comes from the Buddhist Pali term saṅgha (सङ्घ), referring to a Buddhist monastery, which is sēngjiā (僧伽) in Chinese. For want of a better term in Chinese, Christian monks are regularly given the title sēng in Tang era texts too, so our Simon does not have to be a Buddhist monk.

The key to the puzzle rests in learning the extinct Sogdian language, which was well represented among traders from the West in Chang’an. Sogdian was an Iranian language spoken in Samarkand and throughout a region covering today’s Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. It became a Silk Road lingua franca. In Sogdian, the word for ‘rock’ is sang, and this seems to be the origin of the Chinese sēng being used to translate the Petros/Kēfā part of Simon Peter’s name. Thus, Sogdian-speaking merchants and their clergy brought Christianity to China, naming Jesus’ disciple Shem‘ōn Sang, with that literal rocky translation of Kēfā. The scribe of Zūnjīng decided to choose Chinese characters that represented this Sogdian name phonetically. Yet the phonetic transcription is only half the story. The good scribe chose characters that had a meaning that was in harmony with who Simon Peter was. Oddly, the rockiness of ‘Peter’ was transferred to the characters that phonetically represent ‘Simon’, as ‘solid peak’. Twice oddly, a Chinese character for a Buddhist monk that is phonetically derived from the Indian languages Pali and Sanskrit was used to represent the Sogdian word for ‘rock’. I imagine our good scribe thought the character suitable for a holy man, a saint.

P.S. In modern Mandarin Chinese, Simon Peter is Xīmén Bǐde (西门·彼得). The Catholic Church in China uses either Bǎiduōlù (伯多禄) or Bǎiduó (伯铎) for ‘Peter’, and the Orthodox Church uses Péitèrè (裴特若). ‘Simon’ is also often written as Xīméng (西蒙) All are rather phonetic and based on European languages. It is a pity the link with the Syriac/Sogdian of the first to bring Christianity to China has been lost.

P.P.S. Simon Peter was obviously not a monk. Christian monasticism did not really get going until St Anthony in the third century. The fact that Peter was married can be ascertained by the reference to his sick mother-in-law in the gospels (Matthew 8.14, Mark 1.30, Luke 4.38).

P.P.P.S. Speaking of the Sogdian word for ‘rock’, the Sogdian Rock was a fortress in Sogdiana that was besieged by Alexander the Great in 327 BC. Arrian’s Anabasis tells us that the defenders thought the Rock to be impregnable but Alexander employed rock climbers to scale it with flax ropes and tent pegs. Alexander’s prize was to marry the princess Roxana. The Greeks thought her to be the second most lovely woman in all of Asia, which must have given her the hump. She was a Bactrian princess.