My first serious Bible was a pocket

New International Version (NIV), soon followed by a heavyweight NIV study Bible. That translation from 1978 has shaped my knowledge of scripture, and will probably always have a ring of correctness for me because of that. I’m sure many a Bible student would consider my NIV background as something to be ashamed of, even scandalous. I’m no great advocate for the NIV; it’s just my biblical first love. But English-reading Bible students are so often divided and derided over which version they use.

Wikipedia lists 123 English Bible translations, or more, seeing as some are grouped under a single entry. I haven’t heard of a lot of those, and some sound like they are intended for a specific niche in the Bible-reading market. There are clear trends in that list. There are the ‘messianic’ versions, translated by/for Christians who are, or feel like they should be, Jewish. There are the translations that are desperate to be as literal as possible. There are translations linked to particular churches or ‘ministries’, and there are those that pride themselves on interdenominational cooperation. There are the paraphrases that attempt to get to the gist of the meaning, but sacrifice formal equivalence on the way. There are versions that use a particular rendering of sacred names (Jehovah, Yahweh, YWH, Yeshua etc.). There are those that aim to use gender-inclusive language (like my second love, the NRSV). I’m sure that a lot of these Bibles are good, the fruit of hard labour, but I’m sure there are some that are plain awful too. I wonder if there is a special kind of Moses/God complex that drives a pastor/scholar to do a lone Bible translation: this one will be the God’s honest truth. Continue reading “Alphabet soup of Bibles” →

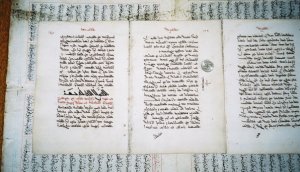

Ad fontes is a Latin phrase meaning ‘to the sources’, a favourite motto of Renaissance humanism. I am particularly thinking of Erasmus of Rotterdam with this phrase, recalling his invaluable biblical scholarship. Renaissance humanism both laid the groundwork for the Reformation and re-engaged with the writers of the early church.

Ad fontes is a Latin phrase meaning ‘to the sources’, a favourite motto of Renaissance humanism. I am particularly thinking of Erasmus of Rotterdam with this phrase, recalling his invaluable biblical scholarship. Renaissance humanism both laid the groundwork for the Reformation and re-engaged with the writers of the early church.