During Holy Week, I had a couple of episcopal moments. On Palm Sunday, six bishops signed a letter in the Sunday Torygraph that didn’t use the word ‘persecution’, but the resulting headlines did, and one sermon I’ve heard since has. Archbishop Rowan felt it necessary to say publically that they should get things in perspective in his Easter Letter: hear, hear!

During Holy Week, I had a couple of episcopal moments. On Palm Sunday, six bishops signed a letter in the Sunday Torygraph that didn’t use the word ‘persecution’, but the resulting headlines did, and one sermon I’ve heard since has. Archbishop Rowan felt it necessary to say publically that they should get things in perspective in his Easter Letter: hear, hear!

The next day, on Maundy Thursday, the Bishop of London felt it necessary refute ‘persecution’ claims in his chrism sermon, but then he went on to talk about how Christians have to fight against the discrimination aimed at us and battle the tide of secularism (this clunkily segued into the twice-repeated materialist motto ‘love is not an emotion’).

On Easter Sunday evening, Nicky Campbell brought out a TV documentary asking whether Christians are persecuted. The show gave fairly free reign to those who wanted to ramp up the persecution fears, but also got the sane voices of the Bishop of Oxford and Theos think-tank in there. I quite liked the clear outline of why the persecution fear exists: that it is based on

- the complex secularising of hegemony,

- increased non-Christian immigration

- and human-rights legislation.

Whereas the fearmongers, like Bishop Michael Nazir-Ali, would point to the secularisation of society as the cause, and crusade for the re-Christianisation of our public spaces, the documentary’s outline gives us more substantial handles for what is happening.

Continue reading “Persecution or privilege: the Church Defensive”

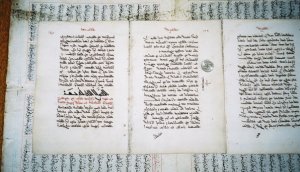

Ad fontes is a Latin phrase meaning ‘to the sources’, a favourite motto of Renaissance humanism. I am particularly thinking of Erasmus of Rotterdam with this phrase, recalling his invaluable biblical scholarship. Renaissance humanism both laid the groundwork for the Reformation and re-engaged with the writers of the early church.

Ad fontes is a Latin phrase meaning ‘to the sources’, a favourite motto of Renaissance humanism. I am particularly thinking of Erasmus of Rotterdam with this phrase, recalling his invaluable biblical scholarship. Renaissance humanism both laid the groundwork for the Reformation and re-engaged with the writers of the early church.