Rather late, I came across this article by a lexicographer researching the etymology of the word ‘risk’. Most dictionaries state that the word comes to English from Italianrisco via French risque. The Oxford English Dictionary attests to it from 1621 in English (as ‘risques’). Its first attestation in Middle French is in 1578, where it is a feminine noun, quickly becoming a masculine noun to mark its testosterone-fuelled approach to life. The Italian rischio is attested in the 13th century, before simply becoming risco.

Although there have been a number of suggestions whence this Italian word came, many are unsatisfactory. The etymology is not certain, but it seems to come from the Middle Persian word rōzīg <lwcyk>, meaning ‘daily bread’ or ‘sustenance’, the ancestor of the Modern Persian word روزى ruzi, and a derivative of the noun rōz <YWM lwc>, meaning ‘day’ (as in nōg-rōz, now spelt نوروز nowruz, Persian New Year).

The Middle Persian word rōzīg was borrowed widely, appearing in Armenian as ռոճիկ ṙočik, meaning ‘salary, wages, pension’. More importantly, its use was spread throughout Southwest Asia in Aramaic, witnessed most importantly by the Syriac ܪܘܙܝܩܐ rōziqā, but also by the Jewish Babylonian Aramaic רוֺזִיקָא rôzîqā (also Talmudic רוּזִינְקָא rûzînqā), and Mandaicraziqa. Syriac also has a clipped version of the word spelt ܪܙܩܐ rezqā, still meaning ‘daily bread’ or ‘sustenance’. It is from this latter form that the Arabic رزق rizqprobably comes (a derivative is one of the 99 Names of God in Qur’ān 51.58, الرزاق ar-Razzāq, the Provider).

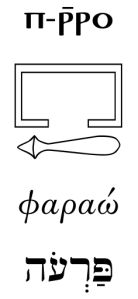

Tracing the route from rezqā/rizq to the Italian risco is less than clear. Neither is the shift in meaning from ‘daily bread’ to ‘chance’ or ‘hazard’. The missing link seems to be the Greek word ῥουζικόν rhouzikon, which appears along with the Arabic rizq in bilingual 7th- and 8th-century papyri from Egypt. Here it describes the grain supply, and particularly a tax paid in food to support Arab troops. In later Greek, the word is attested as ῥίζικον rhizikon, and used in the phrase ἄνδρες του ῥίζικου andres tou rhizikou ‘men of fortune’ to describe mercenaries, and their risky, hazardous existence. The Late Latin resicum or risicumappeared mid-12th century, and almost certainly comes from the Greek, with the meaning ‘hazard, danger’. From there the Italian rischio and risco takes over.

The management of risk is a key economic problem, especially brought into the foreground over recent years. Banking and business have risked too much, and now fear risking at all, leading to the hoarding of value and an inert money system. Faith directs us all to look to God for our needs, be thankful for what we have, and make best use of it. Whether we pray ‘Give us this day our daily bread‘ in the Lord’s Prayer (τὸν ἄρτον ἡμῶν τὸν ἐπιούσιον δὸς ἡμῖν σήμερον ton arton hēmōn ton epiousion dos hēmin sēmeron), or look to God who is ar-Razzāq to provide, people of faith have the useful perspective that we are stewards of earthly resources, not acquirers or competitors. Our risk is faith in providence and blessing.