I’ve just watched Richard Dawkins The God Delusion on the Mo’ Fo’ channel. Last week we had his Faith School Menace; he’s on a roll!

As a Christian in the liberal tradition I believe we need Dawkins. We may often accuse fundamentalists and biblical-literalists of shoddy thinking, but Dawkins is consistent in demanding reasoned answers for all of religion’s claims. In the same way that the traditional process of declaring a person a saint in Catholicism has used a devil’s advocate to ask hard questions to cut through the wishful thinking and groupthink, Dawkins, rather than being feared or scorned, should be appreciated as one who splashes some cold water on the face of sleep-walking religion.

Continue reading “Richard Dawkins: devil’s advocate or phantom menace?”

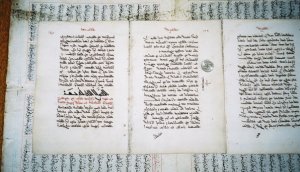

Ad fontes is a Latin phrase meaning ‘to the sources’, a favourite motto of Renaissance humanism. I am particularly thinking of Erasmus of Rotterdam with this phrase, recalling his invaluable biblical scholarship. Renaissance humanism both laid the groundwork for the Reformation and re-engaged with the writers of the early church.

Ad fontes is a Latin phrase meaning ‘to the sources’, a favourite motto of Renaissance humanism. I am particularly thinking of Erasmus of Rotterdam with this phrase, recalling his invaluable biblical scholarship. Renaissance humanism both laid the groundwork for the Reformation and re-engaged with the writers of the early church.