This coming Sunday is the feast of the Epiphany (6 January). The Western Christian tradition focuses on the visit of the magi to the child Jesus, told in Matthew’s Gospel. The Eastern tradition of focusing on the baptism of Christ and the ‘first sign’ at the wedding at Cana (John’s Gospel) has become more common in our observance, leading to a concept of the three things of Epiphany. These three things — the three gifts of the Magi, the water of baptism, and the water become wine — are symbolic unfoldings to us of the nature of who our Messiah is, as our understanding of him grows up from the mystery of incarnation into his good news for the whole world.

Blessings are a particularly important feature of Epiphany. The arrival of the magi at the house (as it is in Matthew’s Gospel) in Bethlehem has lead the church to celebrate the Epiphany as a day for the blessing of the homes of the faithful. Sometimes the blessing is achieved by the clergy visiting the houses of the parish and blessing them with holy water. However, more often water is blessed in church and taken home by members of the congregation for this purpose.

The Sunday of the octave of Epiphany is the feast of the Baptism of Christ (always a Sunday between 7 and 13 January). As an aside, it is moved to the following Monday (8 or 9 January) if Epiphany itself is moved to Sunday 7 or 8 January for pastoral reasons, i.e. no one will come on another day of the week (Epiphany is never moved to a Sunday later than 8 January). Back to blessings, the Baptism of Christ is a great time to bless holy water and use it to bless churches, congregations and anything else within splashing distance. A popular tradition is for the congregation to proceed to the nearest body of water — river, lake or sea — and bless it, often with much splashing.

Other blessed substances have been salt — to remind us to be the ‘salt of the earth’ — and incense, taken to homes to bless them.

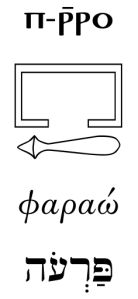

A peculiar and most distinctive tradition from central Europe is the blessing of chalk on the feast of Epiphany. The chalk is blessed in church and taken home to inscribe the lintels of the front doors of homes: for the year 2013, the inscription would be “20 + C + M + B + 13”, with the year intervened by the the letters “CMB”, which either stand for the traditional names of the magi — Caspar, Melchior and Balthasar — or for the Latin Christus mansionem benedicat, ‘May Christ bless the house’. The prayer for the blessing of the chalk is

℣ Our help is the name of the Lord

℟ who made heaven and earth.℣ The Lord be with you

℟ and also with you.℣ Let us pray.

Loving God,

+ bless this chalk which you have created,

that it may be helpful to your people;

and grant that through the invocation of your most Holy Name

all those who with it write the names of your saints,

Caspar, Melchior and Balthasar,

may receive health of body and protection of soul

for all who dwell in the homes where this chalk is used,

we make this prayer through Jesus Christ our Lord.

℟ Amen.

When the chalk is brought home, the inscription can be written on the lintel using these words (symbols in blue are what is written to create 20 + C + M + B + 13)

The three Wise Men,

C Caspar,

M Melchior,

B and Balthasar,

followed the star of God’s Son who became human

20 two thousand

13 and thirteen years ago.

+ + May Christ bless our home

+ + and remain with us throughout the new year. Amen.

Other great Epiphany traditions include the King Cake, a cake, for which there are many different regional recipes, in which a bean, trinket or coin is placed, the finder of which is king for the day. In my native Westcountry, the tradition of blessing the cider orchards in the wassail ceremony is associated with Old Twelfth Night, which is now stuck on 17 January. During the reading of the Gospel for Epiphany, there is a custom of all in the congregation briefly kneeling at the words “and they knelt down and paid him homage” (Matthew 2.11).

After Twelfth Night and Epiphany, as well as the churchly feast of the Baptism of Christ, various other means of marking the beginning of the working year came about, including Plough Sunday (on the Sunday after Epiphany, clashing horribly with the aforesaid) where the plough was brought into church and blessed to begin the agricultural year, and Distaff Day (or Rock Day) a playful marking the beginning of women’s work (and in some places revived as a day to celebrate handicrafts). The first Monday in January was sometimes kept as Handsel Monday, a day for the giving of small gifts, perhaps to neighbours and workmates.

Have a happy and blessed New Year and Epiphanytide.

Related articles

- The Epiphany of Our Lord (pueblodedioslutheranchurch.wordpress.com)

- Solemnity of the Epiphany of the Lord (prepareformass.wordpress.com)

- ‘Wes Hal!’ The final four days of Christmas to ‘Twelfth Night’ and ‘Epiphany’ (Jan 5th/6th) (chandlerozconsultants.wordpress.com)

- Preparing for the Epiphany of Our Lord (anexconsview.wordpress.com)

- Jan. 6: The Feast of Epiphany (examiner.com)

- Follow In The Magi’s Footsteps (marypenich.wordpress.com)

- The Light of Christ: The Epiphany (prayerbookguide.wordpress.com)

- Poetic Liturgy for Epiphany (homespunresources.wordpress.com)