I’ve just spent a restful evening on my sofa watching the last of Bettany Hughes‘s somewhat epic series of documentaries The Ancient World with Bettany Hughes: When the Moors Ruled in Europe. It’s always tempting to criticize this kind of documentary (as I have done in the past; mea maxima culpa!) on what it simplifies or leaves out. However, Bettany Hughes has been helped by having a two-hour time slot on More4 (or Mo-Fo as I’ve heard it called) for each episode.

Never explicitly mentioned, When the Moors Ruled in Europe is clearly set against the 21st-century backdrop of the War on Terror. Aired on the evening before the general election in which two parties — UKIP and the BNP — have anti-Islamic policies in their manifestos, this episode serves as a corrective to the unthinking assumptions of white/European/Christendom superiority. For here we glide endlessly through the mesmerising earthly paradises of Al-Andalus, through Granada’s Alhambra and Córdoba’s Grand Mosque (and not to forget Al-Karaouine University, Fez, Morocco), all set against a backdrop of golden mountains. Here we have liberal, tolerant and highly educated Muslims teaching ignorant Christians about ancient Greek learning before finally falling to the Talibanesque Spanish Inquisition. Although this was a little overwrought in places, there are plenty of moments in the documentary in which the complexities of Christian and Muslim relations and politics are explored, especially setting the Reconquista in the context of stability and cooperation among the northern kingdoms and the reliance of the southern kingdoms on mercenary soldiers.

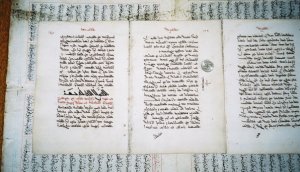

Continue reading “How Arab learning laid the foundations for the European Renaissance”

Ad fontes is a Latin phrase meaning ‘to the sources’, a favourite motto of Renaissance humanism. I am particularly thinking of Erasmus of Rotterdam with this phrase, recalling his invaluable biblical scholarship. Renaissance humanism both laid the groundwork for the Reformation and re-engaged with the writers of the early church.

Ad fontes is a Latin phrase meaning ‘to the sources’, a favourite motto of Renaissance humanism. I am particularly thinking of Erasmus of Rotterdam with this phrase, recalling his invaluable biblical scholarship. Renaissance humanism both laid the groundwork for the Reformation and re-engaged with the writers of the early church.