Tomorrow, 24 March, will be the thirtieth anniversary of the assassination of Archbishop Óscar Romero of San Salvador. San Romero is remembered for his radical faith that compelled him to take a stand against the US-backed right-wing military government of El Salvador. Although often associated with liberation theology, the Marxist theological movement that began in Latin America, Romero rose through the ranks of the church as a staunch conservative, demanding obedience to the church hierarchy and the government, and being openly critical of Marxist priests and the guerilla fighters.

Tomorrow, 24 March, will be the thirtieth anniversary of the assassination of Archbishop Óscar Romero of San Salvador. San Romero is remembered for his radical faith that compelled him to take a stand against the US-backed right-wing military government of El Salvador. Although often associated with liberation theology, the Marxist theological movement that began in Latin America, Romero rose through the ranks of the church as a staunch conservative, demanding obedience to the church hierarchy and the government, and being openly critical of Marxist priests and the guerilla fighters.

However, it was the assassination in 1977 of Romero’s friend, the outspoken Jesuit liberation theologian Rutilio Grande García, who set up base church communities (Christian worker’s communes) in the poorest districts of the country, that was something of an epiphany to him, and foreshadowing of his own death. Romero said, “If they have killed him for doing what he did, then I too have to walk the same path”. Óscar Romero began to speak out against the assassinations and in defence of the poor. He remained critical of the Marxist guerillas, but grew in sympathy for liberation theology.

Continue reading “Óscar Romero on sin and the liberation struggle”

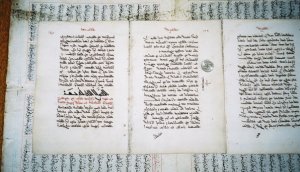

Ad fontes is a Latin phrase meaning ‘to the sources’, a favourite motto of Renaissance humanism. I am particularly thinking of Erasmus of Rotterdam with this phrase, recalling his invaluable biblical scholarship. Renaissance humanism both laid the groundwork for the Reformation and re-engaged with the writers of the early church.

Ad fontes is a Latin phrase meaning ‘to the sources’, a favourite motto of Renaissance humanism. I am particularly thinking of Erasmus of Rotterdam with this phrase, recalling his invaluable biblical scholarship. Renaissance humanism both laid the groundwork for the Reformation and re-engaged with the writers of the early church.