I’ve recently updated my What page, so I thought I would also copy it here as a post for comment.

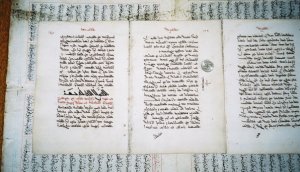

Ad fontes is a Latin phrase meaning ‘to the sources’, a favourite motto of Renaissance humanism. I am particularly thinking of Erasmus of Rotterdam with this phrase, recalling his invaluable biblical scholarship. Renaissance humanism both laid the groundwork for the Reformation and re-engaged with the writers of the early church.

Ad fontes is a Latin phrase meaning ‘to the sources’, a favourite motto of Renaissance humanism. I am particularly thinking of Erasmus of Rotterdam with this phrase, recalling his invaluable biblical scholarship. Renaissance humanism both laid the groundwork for the Reformation and re-engaged with the writers of the early church.

The term ‘humanism’ is only applied retrospectively to this movement. The Oxford English Dictionary dates its earliest meaningful occurrence in the French humanisme of 1765, with the meaning of ‘love of humanity’, with a German reference to Humanismus from 1808 being used to describe the classical syllabus of the gelehrten Schulen (‘learned schools’, grammar schools). Our universities’ humanities divisions and faculties are named after this understanding of humanism. It didn’t take long for the term to acquire two more widely applied senses: the intellectual movement of the Renaissance and a philosophy oriented toward the human. There are a few sparse uses of the term ‘humanism’ to refer to a doctrine that Jesus Christ has a merely human nature (adoptionism, ebionitism and perhaps unitarianism), and Schiller used the term as a name for pragmatism; these are not my doctrines, nor my intended meaning. Continue reading “Ad fontes of Christian humanism” →

Ad fontes is a Latin phrase meaning ‘to the sources’, a favourite motto of Renaissance humanism. I am particularly thinking of Erasmus of Rotterdam with this phrase, recalling his invaluable biblical scholarship. Renaissance humanism both laid the groundwork for the Reformation and re-engaged with the writers of the early church.

Ad fontes is a Latin phrase meaning ‘to the sources’, a favourite motto of Renaissance humanism. I am particularly thinking of Erasmus of Rotterdam with this phrase, recalling his invaluable biblical scholarship. Renaissance humanism both laid the groundwork for the Reformation and re-engaged with the writers of the early church.