Popularly, Catherine is associated with her eponymous wheel that makes it gyratory appearance at fireworks displays, symbolising the first attempted means of her martyrdom. Her legend tells of a young virgin woman who contended in dialogue with the pagan Emperor Maximinus Daia (308–13), successfully converting to Christianity his wife and courtiers, countering their philosophical arguments. The frustrated emperor ordered her tortured to death on the breaking wheel, which broke when she touched it, and so she was beheaded. Angels carried her body to Mt Sinai, where her tomb now lies.

The Catherine legend is problematic for a number of reasons. Although that does not mean that there is no real woman behind the legend, almost none of legend seems to be substantial. Maximinus is a hate figure in Christian history, being ruler of Syria and Egypt and accused of restarting the persecutions against Christians after Galerius, his adoptive uncle, had put an end to Diocletian’s persecutions. Maximinus was also part of the post-Diocletianic struggle for power opposing the party of Constantine (considered the victor of Christendom). It makes sense to see the Catherine legend in this political atmosphere. Surely, there must have been martyrdoms in Alexandria in this period.

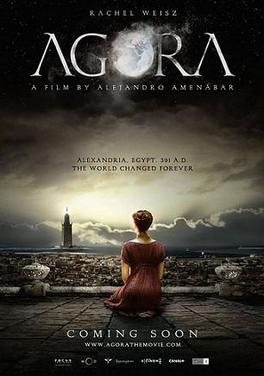

However, the legend seems to have accreted another similar, yet quite opposite, legend: the legend of Hypatia (Ὑπατία). Hypatia lived in Alexandria from the late fourth century, dying in 415. She was a brilliant philosopher of the Neoplatonic tradition, skilled in logic, maths and astronomy. She taught in Alexandria, numbering a future bishop as one of her students. Problematically for the Christian community of the city, she was a pagan. A power struggle for the city was taking place between its bishop Cyril and its prefect Orestes. A mob of monks from the Nitrian Desert had previously attacked Orestes, injuring him. Hypatia was believed to be using her influence as a highly respected professor in favour of Orestes. Believing this, the Nitrian monks, led by Peter the Reader, surrounded Hypatia’s carriage, pulled her out, stripped her and dragged her through the streets. Accounts of her death at the hands of the monks have been variously dramatised in disturbingly sadistic detail. Socrates Scholasticus, a Christian historian of the fifth century, has a sympathetic account of her brutal murder, clearly dismayed by the action of his coreligionists. The legend of Hypatia, however, became powerful anti-Christian propaganda in the hands of the dwindling old Graeco-Roman aristocracy and educated elite. She has remained an icon of reason against the assaults of intolerance and religious extremism. The end of the GW Bush regime in the United States was perhaps as good a time as any to revisit Hypatia, as done in film Ágora by Alejandro Amenábar, with Rachel Weisz as our 21st-century Hypatia.

I can understand the Catherine legend having much to do with guilt-fuelled counter-propaganda against the embarrassing Hypatia legend. It is certainly a disgusting blot on the church if we are guilty of rewriting history to turn our shame into a symbol of our suffering under persecution. Perhaps more sad is the daily severe discrimination met by today’s Christian community in Egypt, the Copts.

I don’t know if it counts for anything, but 25 November is also 29 Hathor in the Coptic calendar, and the height of the month named for the goddess Hathor.

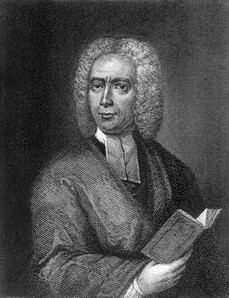

The story of Isaac Watts is over a millennium away from the stories of Catherine and Hypatia. Born in another great port city, Southampton, in 1674, his father was twice imprisoned for holding to nonconformist religious practices: he was not a member of the state church, the Church of England. The Act of Uniformity of 1662 had put severe constraints on those who chose to worship in manner not in accordance with that of the state church. Although showing great academic promise, Watts was unable to study at Oxbridge due to his refusal to accept the rules of the state church. Instead he went to an academy in Stoke Newington, that was set up for the benefit of nonconformists. Many others would have submitted in name alone to the state religion in order to progress in life, but Isaac Watts was steadfast in the independence of his belief.

Watts became a dissenting minister in Stoke Newington. While there he wrote a hugely influential work on logic, which became the official text on the matter in the Oxbridge universities that had denied him on religious grounds. He opposed the imposition of trinitarian doctrine on dissenting ministers by the movement’s conservative wing, upholding their right of each to formulate their doctrine in accord with their reason. This has lead to thoughts that he was a unitarian, something that is not apparent from his writings. Shunned and opposed in life, Isaac Watts is the Father of English Hymnody. The hundreds of hymns he wrote are a unity of passionate faith commingled with doctrinal clarity, unsurprising for a great logician perhaps. However, few in the Church of England who gladly sing When I survey the wondrous Cross or Jesus shall reign where’er the sun realise the radical man behind those words and the intolerant hatred of him and those like him by our church.

So, tomorrow, let’s celebrate Catherine and Isaac, for there is plenty to celebrate. But let us also contemplate Hypatia and Watts the rejected dissenter, better to understand our place in the history of religious intolerance.

Rachel Weisz have that mysterious look and she is very appealing to most men and women “”-