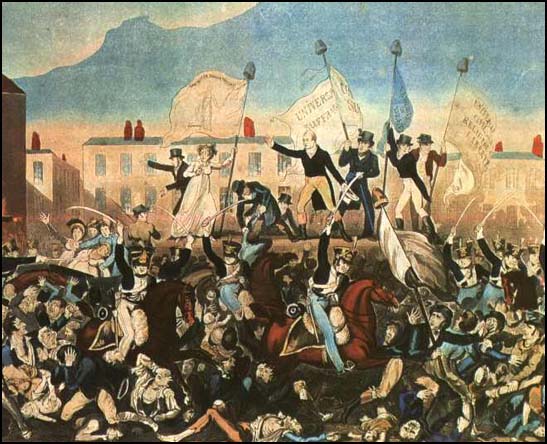

On this day, 16 August, 191 years ago (1819), a peaceful rally of around 60,000 pro-democracy reformers gathered at St Peter’s Fields in Manchester. The crowd of men, women and children were charged by sabre-wielding cavalry, resulting in 15 deaths and 600 injuries. The horrific event is known as the Peterloo Massacre: a macabre, ironic inversion of the heroism of the Battle of Waterloo, met four years earlier, the shame of Peterloo.

On this day, 16 August, 191 years ago (1819), a peaceful rally of around 60,000 pro-democracy reformers gathered at St Peter’s Fields in Manchester. The crowd of men, women and children were charged by sabre-wielding cavalry, resulting in 15 deaths and 600 injuries. The horrific event is known as the Peterloo Massacre: a macabre, ironic inversion of the heroism of the Battle of Waterloo, met four years earlier, the shame of Peterloo.

After the end of the Napoleonic Wars, Britain was in a financial crisis. There were food shortages, wages were slashed and there was massive unemployment. Many British soldiers and sailors returned home to nothing after years of arduous campaign. The food shortages led to increased import of foreign crops, which drove the price of British cereals down. The government’s response was to introduce the first Corn Law, controlling and curtailing the import of crops. This helped keep the price of British cereals artificially high, but severely exacerbated the food shortage. In Parliament, it was argued that steady prices for British crops would protect the wages of agricultural labourers, a rather flimsy excuse for keeping landowners’ incomes high.

Parliament was considered out of touch, elected by a severely antiquated system. Lancashire as a whole, including the great industrial city of Manchester with its surrounding townships, elected two MPs. However, only those who owned land could vote, and they had to travel to Lancaster to cast their vote by public acclamation. In contrast, there were a handful of ‘rotten boroughs’ in which a handful of electors elected two MPs. Reform was clearly needed, yet the ruling class feared the radicalism seen in the French Revolution, and entrenched against it.

The St Peter’s Field meeting was well organised, with contingents meeting around the region and walking together to Manchester. The fine late-summer weather brought many more out, and many women were prominent among the marchers. The organisers of the various contingents made sure that no weapons were carried and hot heads were kept in line with the peaceful reform message. Stewards were drilled for weeks before so that they could control and direct the large numbers. At an estimated 60,000 protesters, the march would have represented about a half of the population of Manchester. The banners carried slogans against the Corn Laws, demanding annual Parliaments (to increase voters’ say over government policy) and secret ballots, and many carried ‘Liberty and Fraternity’ and ‘Unity and Strength’. Many of the banners were topped by a Liberty Cap, the Phrygian cap symbolic of the French Revolution.

Magistrates, fearing a riot or rebellion, assembled around 2,000 cavalry, infantry, special constables and artillery (with two field cannon!). There are many in-depth accounts of the massacre, but it seemed to begin with the local magistrates ordering the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry, an irregular cavalry unit of young, Tory publicans, to assist in the arrest of the organisers of the day. The ill-trained yeomanry got stuck in the dense crowd, and their hatred for the radical poor led to them trampling protesters with their horses, and hacking at them with their sabres. Seeing this, the magistrates ordered the rest of the cavalry to charge the field. Eleven people died on St Peter’s Field, with at least four others dying later. Hundreds were injured by horses’ hooves, sabre wounds or trampled under the pressed crowd. Among the dead were the following

- John Ashton of Cowhill, Oldham, was sabred and trampled on by crowd; he carried the black flag of the Saddleworth, Lees and Mossley Union, inscribed ‘Taxation without representation is unjust and tyrannical. NO CORN LAWS’; the inquest jury returned a verdict of accidental death, and his son, Samuel, received 20 shillings in relief (the equivalent of £40 today).

- Such was their panicked attack, the yeomanry killed a couple of the special constables who were assigned to make a corridor through the crowd for them.

- William Fildes a two-year-old from Kennedy Street was the first victim, trampled under horses hooves as his mother was crossing the road near the protest as the yeomanry galloped to the magistrates’ summons.

- John Lees from Oldham was a veteran of the Battle of Waterloo who was sabred to death on St Peter’s Field.

- Mary Heys of Oxford Rd, Manchester, was severely injured after being ridden over by cavalry; she was mother of six children and pregnant with her seventh at the time of the meeting; the unborn child survived the trampling, but her injuries left Heys disabled and suffering from fits; her unborn child was born prematurely on 17 December, and both mother and baby died.

Peterloo has a powerful legacy. Reporters from Liverpool and London were present at the massacre, and wrote vivid accounts of the massacre that were read widely. The Manchester Guardian, the forerunner to today’s national Guardian, was founded as a mouthpiece for the protest movement, resolute that sabres should not silence the protest. When Shelley heard of the massacre he penned The Masque of Anarchy (‘Stand ye calm and resolute … ye are many — they are few’), which celebrates the might of passive resistance against a violent state, and was often quoted by Gandhi.

In the aftermath, the organisers of the protest were tried, found guilty and given short jail sentences. A test case against select members of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry acquitted them, ruling that justifiable force had been used against an illegal gathering. The government and the Prince Regent publicly lauded the magistrates for their actions in preventing rebellion. The government promulgated the Six Acts, draconian legislation against the perceived threat of radicalism: laws against private militias (although the Peterloo protesters were unarmed), preventing large meetings and gagging radical publications.

Although most British people know nothing of the Peterloo Massacre, the situation of a ruling class that refuses to listen to the people and legislates in the interest of the rich against the poor has resonances today. The death of Ian Tomlinson shortly after having been beaten by a policeman outside the Bank of England last year, shows that the use of state force to quell the frustrations of the people remains with us. The inadequacies of what passes for democracy are once again exposed. It may seem that much has changed, improved, since the Peterloo Massacre, but the struggle for liberty, equality and fair political representation against entrenched privilege that will stop at nothing to share power remains.