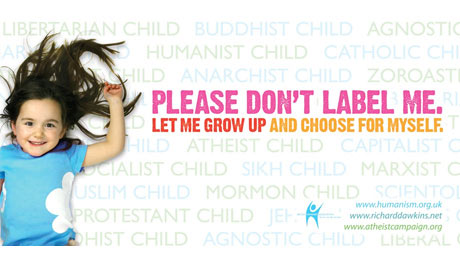

I am completely torn over this. The people who brought you the Atheist Bus Campaign are now bringing us a billboard campaign in which a young child asks us ‘Please don’t label me’. The campaign is the shop window for the brash evangelical wing of atheism, the Dawkins–Hitchens tendency.

First of all, the real political issue behind ‘Please don’t label me’ is faith schools. Regardless of a certain moral panic among secularists, the number and popularity of faith schools in the UK have been increasing. This has happened due to a complex network of reasons that are not all that easy to unravel. I want to talk about the political issues around faith schools first, and then the philosophical issues around the labelling of children. I’ve given the two sections under headings below, so you can skip whatever does not interest you.

Faith schools

The much bigger difference has been the New-Labourism of ‘foundation schools’ which became ten-years old last September. These schools are funded through the local education authority, but have employment, admissions and physical ownership vested indirectly in a charitable foundation. Most of these foundations are religious in nature. Giving other religions parity with the Church of England in running schools is a nod to multiculturalism, and makes certain sense, but the other part is the New Labour mantra of ‘public-private partnerships’ and ‘private finance initiative’. A decade on, PFI has become decidedly problematic and our approach to multiculturalism, even multiculturalism itself, is being questioned.

So, perhaps the Church of England is part of the problem. If we weren’t so eager to hang onto our schools, other religions wouldn’t feel obliged to have schools too. Perhaps it might be better if all schools that received state funding were under local education authority control, as ‘community schools’, and that if religions want to do education they have to do it in the private sector. However, buying out the Church of England alone would mean buying thousands of schools and making hundreds of employees of diocesan boards of education unemployed, and would have little practical effect at the chalk face.

So, perhaps we’re back to the moral panic and media hype about faith schools. After all, the New Atheist movement is almost entirely middle-class and middle-aged, a demographic for whom school admissions is the major battleground on which they fight to get their children a head start.

On the other hand, perhaps it’s time that the public side of public-private partnerships showed some leadership for the money we invest in faith schools. This could involve moves to scrap any religious qualifications for admissions, scrap ‘religious tests’ for the employment or promotion of certain teaching posts (which range from asking applicants to be ‘sympathetic’ to requiring membership of a specific religious group), allowing only the LEA syllabus for religious education (banning the ‘faith-based RE’ option exercised in a minority of faith schools), and no longer accepting that assemblies can be ‘worship’. I think such moves by an education secretary would win such wide support in society that the Church of England would have to give in, and then other religious groups would be left in a reactionary minority.

Labelling children

At the Reformation, many reformers responded to the Enlightenment by declaring that a faith commitment can only be made once one is old enough to formulate it for one’s self. This led them to reject infant baptism and call for the baptism of adults only, and the rebaptism of those who were baptized as babies. The modern response from those, who like me, baptize babies is that this turns faith into a rational proposition and something to be arrived at rather than marking the commencement of a journey of faith. Maybe it’s no surprise then that the Evangelical Alliance have supported the posters. It is also interesting to see the comments on the Comment is Free article where the non-religious are going through the same arguments again: either labels require rational assent and children shouldn’t be labelled, or that parents have an important role in passing on what is important to them to their children. Atheism, like Protestantism, is based on the Enlightenment ideals of rational formation. Whereas sociologists (Weber for example), along with baptizers of infants, would point to the importance of the childhood ethos that leads to that rational formation.

At the Reformation, many reformers responded to the Enlightenment by declaring that a faith commitment can only be made once one is old enough to formulate it for one’s self. This led them to reject infant baptism and call for the baptism of adults only, and the rebaptism of those who were baptized as babies. The modern response from those, who like me, baptize babies is that this turns faith into a rational proposition and something to be arrived at rather than marking the commencement of a journey of faith. Maybe it’s no surprise then that the Evangelical Alliance have supported the posters. It is also interesting to see the comments on the Comment is Free article where the non-religious are going through the same arguments again: either labels require rational assent and children shouldn’t be labelled, or that parents have an important role in passing on what is important to them to their children. Atheism, like Protestantism, is based on the Enlightenment ideals of rational formation. Whereas sociologists (Weber for example), along with baptizers of infants, would point to the importance of the childhood ethos that leads to that rational formation.

Raising children is not a value-free activity, and education, however it is done, involves the imparting of a ethical framework to children, even the imprinting of such. Education and child-rearing is always based on some such ethical framework however ill-conceived or fragmentary. Thus, there is no such thing as a childhood exempt from values, and these values have labels attached. Although there is plenty of room for parental expression of these values (for good or ill), when education takes place beyond the family unit society’s collective values are used (for good or ill). In a multicultural society, we recognise differing, even conflicting, values, and, if we have no overarching ethical framework, this leads to fragmentation. This fragmentation is demonstrated by the idea of a plurality of labels being a Bad Thing. In this light the poster campaign is simply part of a moral panic about the fragmentation of society, admittedly done in a more United Colours of Benetton than Daily Mail way.

Ideas, values, philosophies and religions permeate every part of our society. All of us are participants in labelling however apathetic, and no child can be exempt without living in a bubble. What the New Atheists have done is put a soundbite on a billboard. Its philosophical depth is as shallow as much of their arguments (a discredit to the honourable traditions of atheist thought). There is a poorly articulated campaign behind the slogan, which could positively been seen as a call to develop an overarching ethical framework within which state education should function, but it is more likely to find greater engagement with middle-class moral panic over fragmentation in society, getting their children into the ‘best schools’ and an old idea that religion isn’t a nice dinner-party topic for conversation (leading to general desire to disengage). I’m sure many BoBos (bourgeois bohemians) will find the poster smugly satisfying, but in the end it is philosophically empty at best, reactionary and monoculturalist at worst.

In the end, I’m still torn. I think there’s an important discussion to be had here, but the manner of the proposition means that it’s not going be had.

Jonathan Bartley approaches this question differently in an article for Ekklesia, by suggesting that the campaign should have used the slogan “How would Jesus run a school?” to sort out the sheep from the goats. I think this is going in the same direction as my own thinking, encouraging faith schools to be radical through the opening up of discriminatory practices. I mention it, because his replacement slogan really does shame faith schools to change their ways.

Pingback: Richard Dawkins: devil’s advocate or phantom menace? « Ad Fontes