Advent is well come nigh! A truth calendrical and etymological. So, I thought I might delve into one obscure word in this season’s vocabulary.

Advent is well come nigh! A truth calendrical and etymological. So, I thought I might delve into one obscure word in this season’s vocabulary.

The word ‘Maranatha‘ appears in I Corinthians 16.22 and Didache 10.6. Respectively:

εἴ τις οὐ φιλεῖ τὸν κύριον, ἤτω ἀνάθεμα. μαράνα θά.

If anyone does not love the Lord, let them be anathema. Marana tha.

ἐλθέτω χάρις καὶ παρελθέτω ὁ κόσμος οὗτος. Ὡσαννὰ τῷ θεῷ Δαυείδ. εἴ τις ἅγιός ἐστιν, ἐρχέσθω· εἴ τις οὐκ ἔστι, μετανοείτω· μαρὰν ἀθά· ἀμήν.

May grace come and this world pass away. Hosanna to the God of David. If anyone is holy, let them come; if anyone is not, let them repent; maran atha; amen.

It is an Aramaic phrase (although Luther tried to twist it into a totally different Hebrew phrase — מָחֳרַם מָוְתָה māḥăram mothâ, ‘devoted to death’). It was once thought to be a curse word, associated to its preceding anathema in the I Corinthians verse, but is clear that the ancient authors who promoted this interpretation had a rather hazy understanding of the phrase. However, that verse is part of Paul’s concluding prayer for the Corinthians, and forms a rather disjointed collection of prayed aphorisms:

- All the brethren send greetings.

- Greet one another with a holy kiss.

- I, Paul, write this greeting with my own hand.

- If anyone does not love the Lord, let them be anathema.

- Maranatha.

- The grace of the Lord Jesus be with you.

- My love be with all of you in Christ Jesus.

In the Didache, ‘Maranatha’ appears as part of the doxology of the eucharistic prayer. The short phrases here have been considered by some to be meant to be recited in versicle and response form:

- Celebrant: May grace come and this world pass away.

- Congregation: Hosanna to the God of David!

- Celebrant: If anyone is holy, let them come; if anyone is not, let them repent.

- Congregation: Maranatha! Amen!

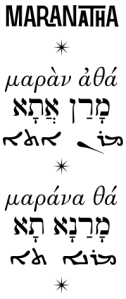

The odd use of this Aramaic phrase in Greek texts seems to be a liturgical formula handed on by the first Aramaic-speaking Christians. Just as today’s Syriac Orthodox liturgy has the regular prayer cadence ܒܪܟ ܡܪܝ ܐܡܝܢ barrekh Mor amin (‘Bless, my Lord, amen’), ‘Maranatha’ is a doxological ‘Come, our Lord’ or ‘Our Lord is come’. Its exact meaning depends on how the phrase should be broken down into two words:

- either māran ăthā

- or māranā thā.

The earliest manuscripts don’t help as they have no word break or accents. Whether it is māran or māranā, the first word means ‘our Lord’, from mārē, ‘Lord’, and the possessive suffix -an or -anā, meaning ‘our’. The other word, as ăthā, is the perfect tense of the verb ‘to come’ — ‘he has come’ — as thā it is the apocopated imperative of the same verb — ‘come!’.

Patristic scholarship favoured the division māran ăthā, but, if this can only be read as ‘our Lord has come’, it lacks the apocalyptic character we might expect (although this fits with the spirit of the alternative opening to the modern eucharistic prayers: ‘The Lord is here./His Spirit is with us.’). Modern scholarship has tended to favour the division māranā thā to get us the meaning ‘our Lord, come!’. The encouragement for this interpretation is usually gleaned from placing the phrase parallel to Ἀμήν, ἔρχου κύριε Ἰησοῦ (Amēn, erchou kyrie Iēsou, ‘Amen, come Lord Jesus’) of Revelation 22.20, and related to the eucharistic context of ὁσάκις γὰρ ἐὰν ἐσθίητε τὸν ἄρτον τοῦτον καὶ τὸ ποτήριον πίνητε, τὸν θάνατον τοῦ κυρίου καταγγέλλετε ἄχρι οὗ ἔλθῃ (hosakis gar ean esthiēte ton arton touton kai to potērion pinēte, ton thanaton tou kyriou katangellete achri hou elthē, ‘So, everytime you eat this bread and drink the drink, you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes‘) in I Corinthians 11.26.

The first-person plural pronominal suffix is -anā in Biblical Aramaic, Qumran Aramaic, Judaean Aramaic and the standard Targums, whereas -an is found in the Midrashim, both Talmuds, Samaritan Aramaic, Christian Palestinian Aramaic and Syriac. So which Aramaic does the word come from? Most assume Judaean Aramaic, but I have a suspicion that the source might have been the dialect of Antioch (-an?). Either way, by the time the Church Fathers got involved in the debate, the Aramaic speakers they knew used -an.

The verb ăthā ‘to come’ is far more problematic: is it an imperative or an indicative? If it’s indicative, it’s tense is perfective, ‘he has come’, although it is possible in Aramaic that this has what we would translate as a present-tense sense ‘he has come, and is now here’. The Syriac Peshitta supports this word division with its ܡܪܢ ܐܬܐ māran ethā.

If it’s imperative, ‘come!’, there are problems with the spelling. The apocopated form thā, that is often favoured today doesn’t exist in any variety that has the ending -anā. Then ăthā is the usual form for the imperative. The word ‘maranatha’ could then be achieved by the ellision of the reduced vowel into the preceding, strong ā: māranā-[ă]tha.

It seems ‘Maranatha’ is a fossilised phrase from the earliest prayers at the church’s eucharistic gathering, a prayer that Christ might come and be round the table where his disciples gather to feast his memory. What better phrase for Paul to write to the Corinthians, after teaching them of the eucharist, to share with them this symbol of Christ-fellowship? Come, our Lord, be among your people.

Pronunciation: [mɑˈranɑˌθɑ], maa-RA-naa-THAA, where capitals are stressed syllables, and ‘aa’ is like the first vowel in ‘father’, ‘a’ is as in ‘fat’.

A PDF version of this article is available at www.garzo.co.uk/documents/maranatha.pdf.

Thanks for this great post and the explanation of the Aramaic phrase maranatha. As you point out, there is ambiguity between whether you take this as the Aramaic “maran atha” meaning “our Lord is coming”, or the Aramaic “mara natha” meaning “the Lord will come.” Perhaps it is this very ambuiguity in the Aramaic, where the immediacy of the Lord’s coming is emphasised, that leads to it being such an important phrase, and one which was preserved in the Greek text. You could combine the Aramaic interpretations to mean “Our Lord will come, and is (already) coming.”

Hello, Aramaic Scholar! I didn’t mention a division as ‘mara natha’ (I mentioned ‘maran atha’ and ‘marana tha’). I didn’t mention it because I don’t think it is a viable candidate. The first issue is with ‘mara’ in the absolute state, its meaning is almost certainly indefinite: ‘a lord’. That’s problematic, as the two key texts are clearly talking about Christ. The second problem is with the form of the imperfect of the verb. Not all varieties of Aramaic have a nun as the preformative to the 3rd-person masculine singular; a good few have a yod instead. As a pe-alap verb, all relevant varieties of Aramaic lengthen the first vowel too. Thus, the only forms we might expect are ‘yēthā’ (Biblical Aramaic, Targums and Talmud) and ‘nēthā’ (Syriac). In the end, if the imperfect were behind the phrase, it would have been spelt differently in Greek (with ēta), and it leaves us with the problem of how we interpret the absolute state ‘mara’.

I like the idea about ambiguity leading to a double meaning. However, it seems that the different divisions are dependent on which variety of Aramaic is the origin, and that the two divisions cannot coexist in the same variety. Or did the composers of this phrase get clever and combine Judaean and Antiochene Aramaic? Probably not!

Reblogged this on My BlogSocialDynamos.WordPress.com.